Why does it take so long to build the TTC?

On political footballs, penny pinching, and endless lawsuits

Gooood morning and welcome back to this week’s edition of the Tangent Factory! I wasn’t sure if you guys would like the piece I wrote last week about why the TTC is so poor, but it seemed to go over well. This week, I’m back to answer the age old question of why it takes so long to build transit in Toronto. I don’t know if I have the solution for you, but hopefully you find this post at least somewhat informative.

If you do, drop me a like, a comment, and dare I say it again, subscribe!

Last year, I went to Florence and saw the Vasari Corridor. Built in 1565, it’s a feat of engineering comprising a series of above-ground passages that extend across several buildings, a river, and into homes on the other side. Tired of walking among the peasants, Cosimo Medici, the ruler of Florence, commissioned the passage as a way to transport himself easily from one side of the city to the other without being seen by the riffraff. And it took only five months to build.

Things have a changed a lot since renaissance Florence (we have better labour protections, for one thing), but seeing that tunnel really made me wonder why it takes so damn long to build transit in Toronto. And that’s what we’re talking about this week.

What is the Eglinton Crosstown?

No project better exemplifies Toronto’s crawling pace of construction than the Eglinton Crosstown LRT. First proposed in 2007 under Mayor David Miller’s “Transit City” development plan, the Eglinton LRT was supposed to be one of several light rail streetcars connecting parts of Toronto poorly served by the subway. In 2010, new mayor Rob Ford scrapped many of the “Transit City” projects to focus on subways and cars, catering to his suburban voter base. Ford kept the Eglinton line, however, as construction was already slated to begin in 2011. Crown corporation Metrolinx was tasked with managing construction.

Originally, the Eglinton LRT project was set to be completed in 2020, with a budget of $9.1 billion. But here we are in 2024 with no LRT, just a “97% complete” rail system, a bunch of technical glitches, and a budget that has now reached over $12 billion. Metrolinx refuses to release an opening date until three months before opening. And who knows when that will be?

Meanwhile, Montreal’s REM light rail system began construction in 2018, and was open to users by 2023.

Why do things take so long in Toronto?

Election flip-flopping

To answer this question, we’ll begin with the obvious culprits. Transit projects are socially and technically complicated beasts. Not only do we need to figure out how to physically build trains and tracks, but we also need to figure out where they should go to maximize peoples’ happiness and minimize their pissed-offness.

Depending on who wins each election, the government’s opinion on how to optimize these conditions will change. The work Miller started with “Transit City” was mostly undone by good old-fashioned politicking when Ford won the next election.

Wallet-Clutching

In an article for Spacing Magazine, John Lorinc describes how budget concerns at city hall can delay transit construction for years, and often end up making things more expensive, not less.

Ingrained in Toronto’s culture, argues Lorinc, is the idea that “growth should pay for growth”. Basically, development should not occur unless it can immediately produce more revenue. This is why a condo building with a pay-to-park garage can be approved more easily than a park or bike route. While sensible in theory, dogmatically insisting that public infrastructure should make money (as opposed to say, facilitate better movement for residents) really just causes us to delay building things that we need until they become more expensive and difficult to build.

Lorinc points to the condo-filled neighbourhoods near Toronto’s waterfront as evidence:

“The Queen’s Quay LRT is a prime example. When we finally have enough loonies in the municipal cookie jar, much of the waterfront/port lands development will have happened, meaning the LRT construction must compete with the area’s new residents, who will be driving far more than they should be because, well, growth pays for growth so there’s no LRT.”

Complex Infrastructure

Even when we can agree on what projects should be built where, there are still technical challenges. Building under major intersections, alongside existing subways tracks can be incredibly difficult from an engineering and logistics perspective.

Navigating the Yonge and Eglinton intersection was a major driver of delays in the Eglinton Crosstown construction. Building under a major intersection that already has a subway tunnel underneath and a dense streetscape of storefronts is no easy feat. For the four years I attended highschool in that area, it was like walking through one giant construction pit.

Transit Orgs Fighting in Court

But these are challenges that face every city, and Toronto seems to have some unique difficulties.

If you’ve been following the Eglinton Crosstown saga, you probably remember that last year Crosslinx Transit Solutions (CTS), the coalition of construction companies building the LRT line, sued Metrolinx.

If you’re lucky enough to have skipped that debacle, here’s the gist:

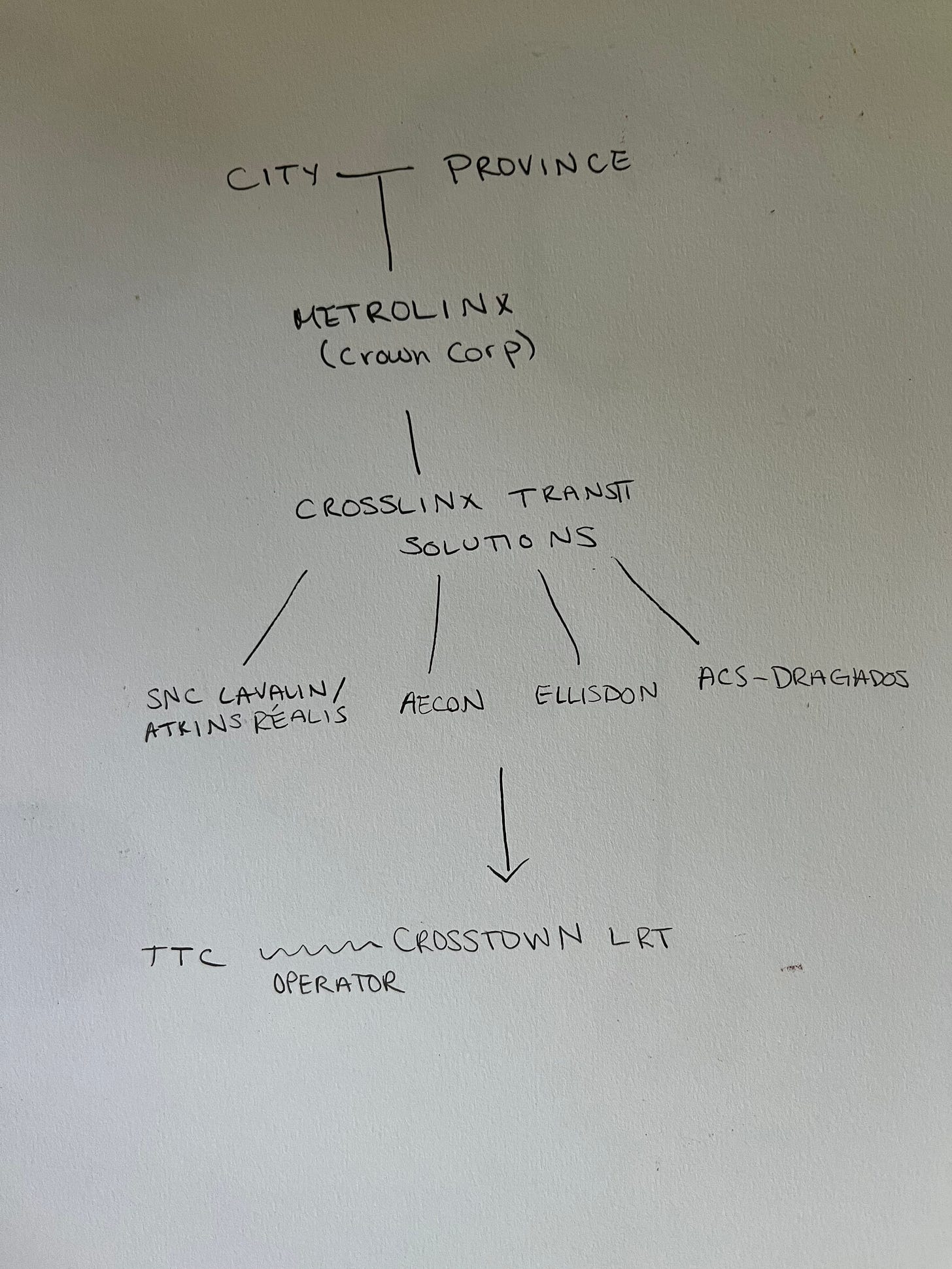

The city and the province commissioned and funded the Eglinton Crosstown, appointing Metrolinx to manage the project. But, since Metrolinx is not a construction company, they had to contract several companies to actually build the line. These companies formed a coalition called Crosslinx Transit Solutions. The TTC would be the operator of the line when it was complete, but has not been involved in building the line, except to make requests for how it should be constructed. I’ve made a little map below.

Around March of last year, CTS sued Metrolinx, claiming that they were submitting changes that violated the scope of their contract. Susan Sperling, CTS Spokesperson, justified the suit by claiming that last-minute changes without proper contract amendments were raising costs for CTS:

"Metrolinx has refused to manage or take ownership over these late changes requested by the TTC despite the undeniable continual impact on the Project schedule. This has resulted in delays to the Project outside our control and significant costs overruns which CTS has continued to incur."

Metrolinx CEO Phil Verster disagreed, accusing CTS of "looking for new ways to make financial claims" and engaging in “delay tactics”.

There are probably more reasons than these to explain the sluggish pace of Toronto’s development, but these should provide a good jumping off point. Say what you will about the Medicis, but they got stuff built…