Happy Saturday and welcome back to the Tangent Factory! If you’re new here, Tangent Factory is a newsletter where I talk about economics, culture, and occasionally my real life. This week, I’ve been thinking about optimism and pessimism, and which is (generally) better. Like all absolute questions, this one doesn’t have an absolute answer. But I enjoyed reading on it and I hope you will too :)

A few weeks ago, I picked up a copy of Morgan Housel’s book, The Psychology of Money.

I’d recently graduated college and figured it might do me some good to come up with a plan for my finances in the coming months, and maybe even the rest of my life.

I soon learned, however, that The Psychology of Money is not really a personal finance book. It offers no practical advice on what type of stocks to buy or what do when interest rates dip. Instead, it operates on the premise that being “good with money” isn’t about knowing the most about investing, but about understanding how your psychology influences what you do with the money you have.

Throughout, Housel’s advice is equivocal. There’s not one right way to manage your money. Different strategies help different people sleep soundly night, and at the end of the day, that’s what money should help you do.

On one point, however, Housel is adamant: when it comes to investing, we should all be optimists.

“Assuming that something ugly will stay ugly is an easy forecast to make. And it’s persuasive because it doesn’t require imagining the world changing. But problems correct and people adapt. Threats incentivize solutions in equal magnitude.”

Basically, unless you truly believe the entire world’s economy will undergo a long and permanent decline where we completely cease to create and sell new stuff, a person who expects to live a long time should bet on the future1.

In other words, it ain’t over til it’s over.

In finance and in life, most of us would love to be able to predict the future. But alas, we can’t, and so we argue instead over the best approach to prepare for it. Most people fall broadly into two camps.

Optimists believe that even if things are bad now, and even if they get worse, at some point they are likely to get better. And we should place our bets accordingly.

Pessimists believe the opposite. That even though the sun is shining today, tomorrow it may rain, and we’d all better stock up on umbrellas.

Most of us will fall into both camps at some point our lives (and probably at some point today), so Housel’s assertion that optimism was not just the better but the more rational and accurate position was an interesting idea to me.

Are optimists really more rational than pessimists?

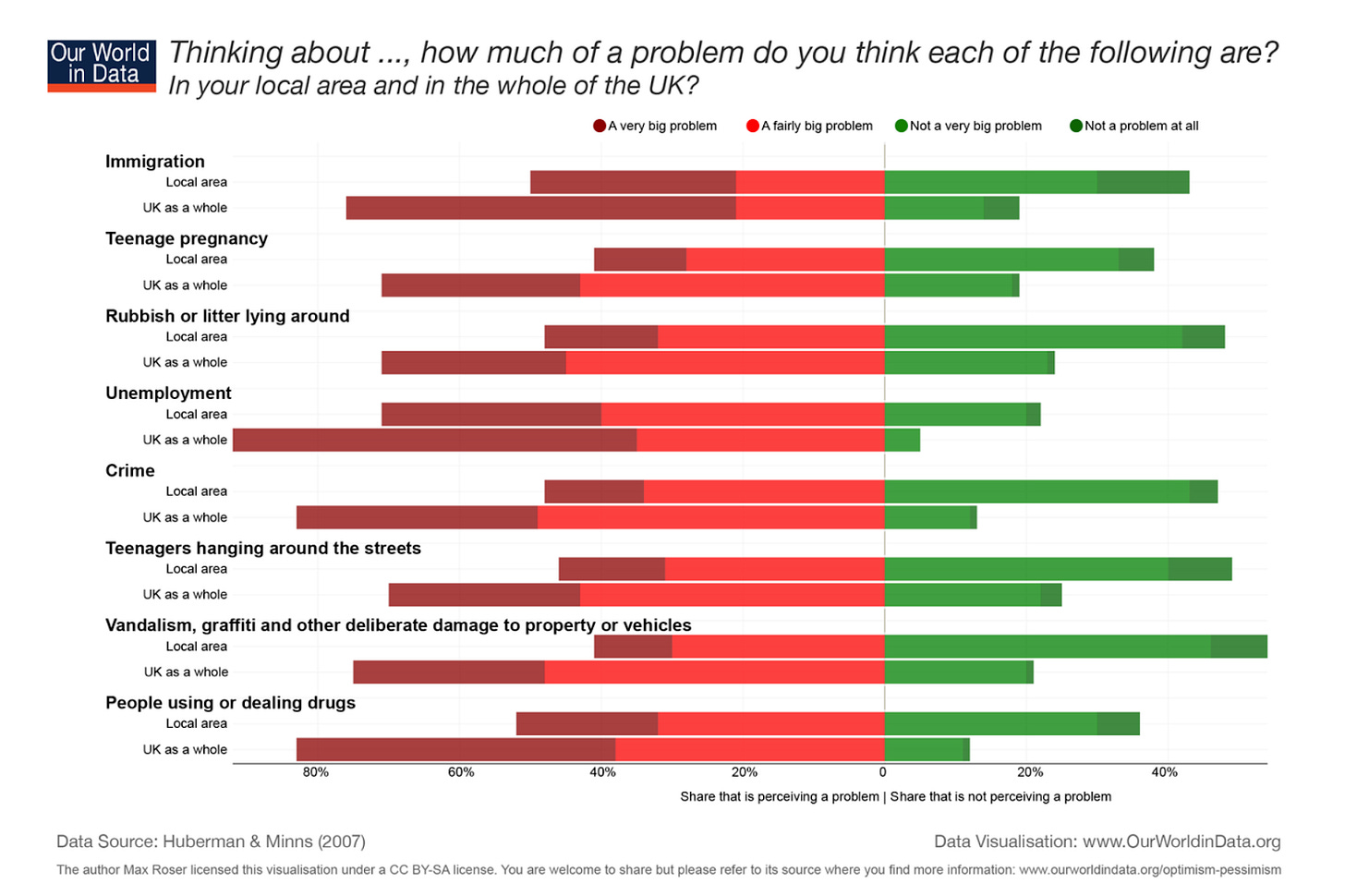

A smidge of reading led me to a page compiled by Our World in Data, showing just how irrational our optimistic and pessimistic beliefs can be.

For example, people tend to hold more positive beliefs about social issues in their immediate communities than in their country as a whole. Though its possible that some of these “local optimists” hold accurate perceptions, it’s almost impossible for them to all be correct. If everyone believes that problems are worse in someone else’s neighbourhood, then there’s no neighbourhood left for the problem to actually be worse.

Here’s another example. In 2023, only 23% of Americans thought the country was doing “good” or “excellent” economically, despite 40% of Americans saying their personal finances were in “good” or “excellent” shape.

There are, of course, external factors that may drive this irrationality. We tend to learn about faraway places through media, which often comes with a bias toward negative news. Our experiences of our own lives tend to be more balanced.

People can be irrationally optimistic as well:

65% of Americans believe they possess above average intelligence, which if you’ve taken one elementary school class on probability, you’ll know is impossible.

We tend to believe we have lower odds of facing random disasters like injuries or accidents than other people. Of course, random accidents, by definition, happen to all people with equal probability.

In general, Our World in Data finds that people tend to be optimistic about their individual futures, and pessimistic about our social futures.

These biases can be largely attributed to two factors:

Perceptions of personal agency

Feelings of optimism are highly correlated with individuals’ sense of agency. If we feel that our actions will have an effect on an issue, we feel more optimistic and in control of a situation. Those with low perceptions of agency tend to feel that the future is out of their control and are consequently more pessimistic.

Gaps in information

When we have first-hand knowledge about a topic, we are more likely to accurately predict its future trajectory and feel that this issue can be managed. When we receive knowledge through secondary sources with a negative bias (i.e. news media), we are more likely to adopt a negative view of this issue. This can go both ways, but people with more accurate information on a problem do tend to be more optimistic about that problem’s future.

Does it matter?

Clearly, both optimists and pessimists can be equally irrational in their views. Does it matter, then, which outlook a person holds?

Some would argue it does.

Optimism and pessimism aren’t just about how we view the world, but how we engage with it. Someone who is optimistic about their ability to win at a slot machine will play more turns than a pessimist. And will pay dearly for it. But someone who is optimistic about the problems in their city is more likely to take action because they believe change can be achieved. If we are irrationally pessimistic about our future, we may do less to ensure positive outcomes and trigger the very negative outcomes we worried about in the first place. Cynicism breeds passivity, while optimism encourages action. Both have their place, but we need to know when each one is appropriate.

So, was Housel right? Are optimists more rational than pessimists?

Yes and no.

But if both optimists and pessimists can be irrational, I think I’d rather be the optimist.

If you plan to retire tomorrow, it goes without saying that you might want to be a little more shortsighted in your planning. Those people are allowed to be pessimists.