How many people does it take to invent a light bulb?

The “adjacent possible” and why so many similar discoveries happen at the same time

Hello and welcome back to another week of the Tangent Factory!

If you’re new here, the Tangent Factory is a weekly newsletter written by me, Sara. Here, I talk about economics, culture, and sometimes things from my real life. This week, I wanted to dig into the theory of the “adjacent possible,” and use it to explain why so many technological breakthroughs happen at the same time.

If you like what you find here, you can subscribe for free and receive these little letters straight to your inbox! You can also find me on Instagram (@tangentfactory)

When we talk about who invents things, most believe each tool or object must have a single inventor. What seems less salient in public narratives is just how many inventions actually have multiple inventors.

If I asked you who invented the light bulb, you’d probably tell me it was Thomas Edison. But while Edison is the most famous inventor of the lightbulb, he is not the only person to have invented it.

In fact, by 1879, the year that Edison patented his commercial light bulb, Alessandro Volta, Humphrey Davey, and Joseph Swan had already developed incandescent lightbulbs. Edison’s bulb was more efficient and saw greater commercial success, but he wasn’t the sole inventor.

How did these people, working in separate labs, invent the same tool at the same time?

Someone with a basic knowledge of history might point out that these scientists weren’t hermits, and their ideas were shared and discussed widely. While they worked on their prototypes independently, they were also borrowing, modifying, and testing one another’s ideas. Innovation does not happen in a vacuum. It happens in an ecosystem.

We could stop there. The fact that many people work on the same problems at the same time provides a pretty plausible explanation for the simultaneous-inventor phenomenon. But in my opinion, it’s an incomplete theory. And I have a better one for you.

The Adjacent Possible

Coined by the American Medical Doctor and Academic, Stuart Kauffman, the “adjacent possible” is the simple idea that at a given point in time, there is a finite set of choices available to individuals, organisms, organizations, or productive processes, and that these choices open new possibilities and foreclose old ones.

Drawing on his expertise in biology, Kauffman explains that a species’ evolutionary path is not predetermined. A creature living between a river and a forest might evolve to swim or to fly. It has choices. But once it becomes a fish, it cannot become a bird, and vice versa1. The choices this creature makes opens up new possible “choices” – will it be a big predator fish or a small herbivore fish? – and forecloses others – it can no longer breath pure oxygen.

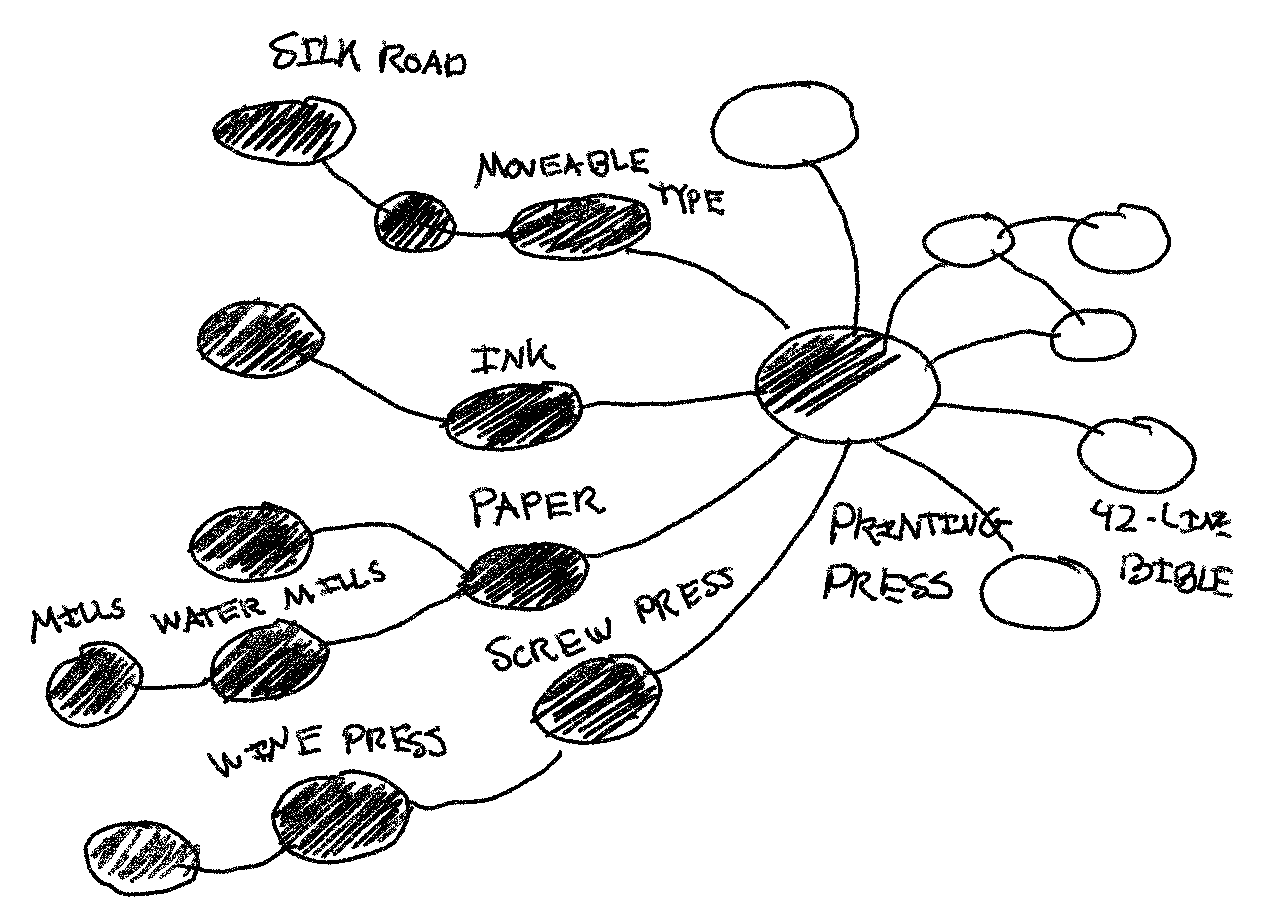

Kauffman shows how we can extend the same logic to human innovation. The printing press was a combination of a wine press, paper, ink, and moveable. This combination created new possibilities for books, newspapers, and information sharing. But it also foreclosed old ones. Scribesmanship faded to obsolescence, and we will never know what new combinations may have come had we followed that branch of the tree.

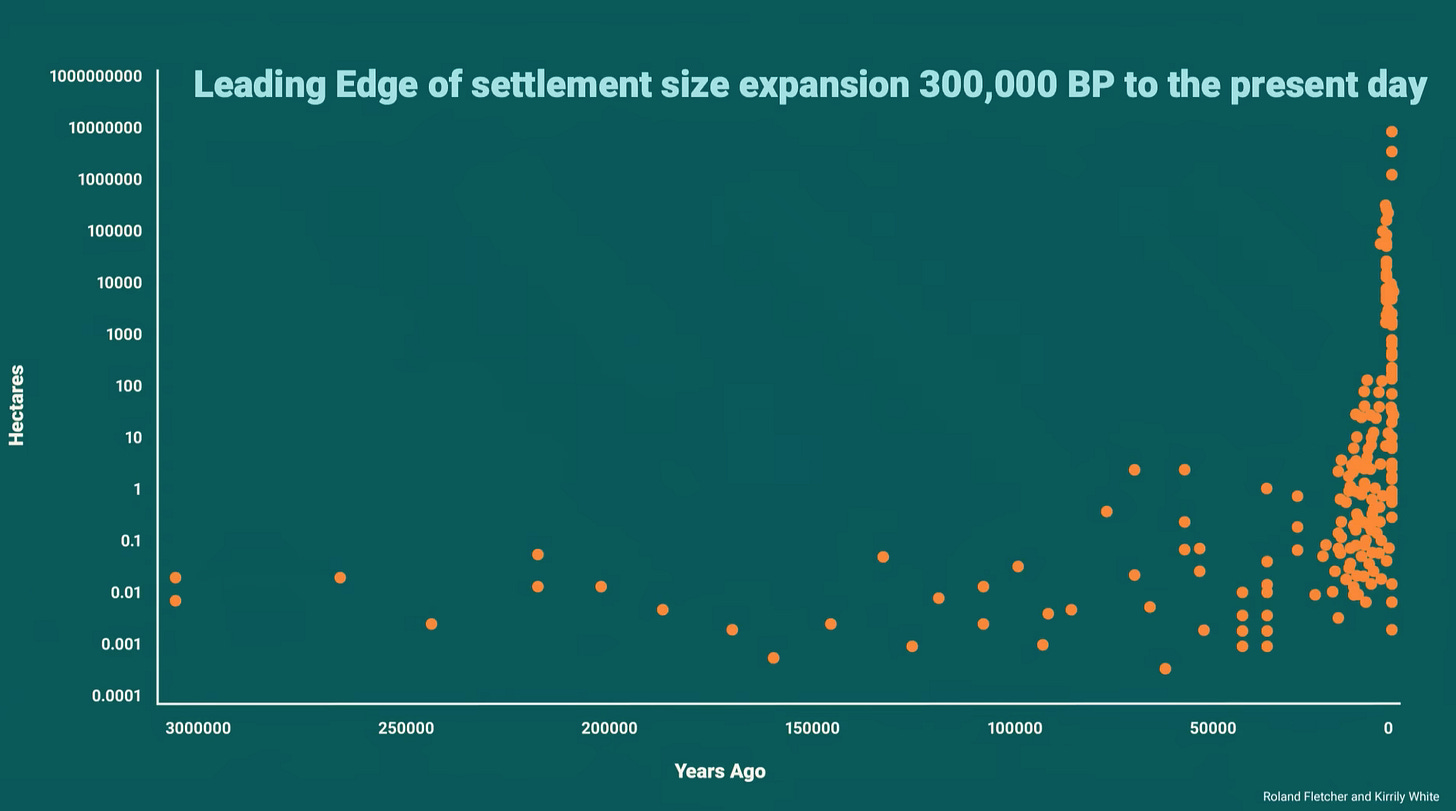

Every single object, argues Kauffman, has multiple potential uses, each of which might transform the way we live if used or combined with another object in the right way. Crucially, this spectrum of possible uses increases exponentially, not linearly. This means that technological progress is more likely to follow a hockey stick curve of growth, much like the one seen in the growth of new species during the Cambrian explosion. In fact, we are likely already well into an accelerated stage of growth in innovation; Kauffman notes that the size and frequency of human settlements today already surpass what would be expected if historical settlements expanded linearly (shown below). And if that doesn’t persuade you, think of the scale of technological change between 1990 and today versus that between 1890 and 1924.

But the adjacent possible is as much about limits as it is about possibilities. It is easy to imagine endless futures, each different from the other. But in real life, we get one future. Like in a game of chess, actions cannot be undone, and some moves make others impossible. If you kill the Queen, she can no longer protect the King. We don’t get do-overs, only re-combinations of the things that exist in the present.

Personal Adjacent Possibles

Kauffman primarily uses the idea of the adjacent possible to think about climate change and tools to address biodiversity loss, but the theory can be applied to pretty much everything from culture, to public policy, to our personal lives.

Though Kauffman is not too concerned with the career satisfaction of ambitious professionals, others have eagerly applied his frameworks to the question of how to do work you love while also doing less of it.

I’m thinking in particular of productivity guru and Georgetown University Professor of Computer Science, Cal Newport.

In his 2010 book, So Good They Can’t Ignore You, Newport makes the controversial case that “following your passion” is bad career advice. Instead, he argues that the things that make us happier - control over our time, positive relationships with colleagues, and a sense of purpose - are better achieved by honing skills that differentiate us from others, thereby increasing demand for our skills in the labour market and allowing us to increase control over our time and command higher wages.

Finding and nurturing high-demand skills, however, is easier said than done. For much of our early careers, we learn skills that have already been mastered by someone else. This is not a bad thing. We are getting up to speed, developing expertise. At some point, however, differentiation becomes necessary, and this is where Newport argues we must lean into the adjacent possible.

Combining pre-existing skills in new ways - by inventing a new product, opening a business with a unique value-proposition, or testing novel approaches to problem solving can all open doors to financial and lifestyle rewards. They require some degree of risk and innovation, however, pushing past the limits of what we are currently able to do and into the combinations of our skills that have not yet been tested.

In a culture that lionizes youth and early achievement, it can seem unnatural to view our careers as a slow march toward our own unique adjacent possibles. More often, young people are encouraged to find the fast route to success or default to viewing work as something to trudge through and endure. The adjacent possible, however, encourages a more patient and values-driven approach to career development.

Whether you think the idea of the adjacent possible is interesting, or a bit of a truism, I like its elegance in explaining the trajectory of an entities evolution. It manages to make a case for both optimism, through the ever-expanding possibilities of future combinations, and caution, by showing us that the we don’t always get second chances, and a bad choice today might worsen our options tomorrow.

Once it becomes a human, it cannot do either.